By Fredrik Dahl

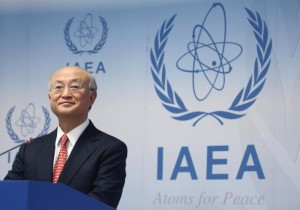

Credit: Reuters/Heinz-Peter Bader

VIENNA Mon Feb 3, 2014 2:30pm EST

(Reuters) – The U.N. nuclear watchdog says it wants Iran to clarify past production of small amounts of a rare radioactive material that can help trigger an atomic bomb explosion, but which also has non-military uses.

The comment about polonium by U.N. atomic agency chief Yukiya Amano at a weekend security conference in Munich suggested the issue may be raised at talks between his experts and Iranian officials on February 8.

It also signaled his determination to get to the bottom of suspicions that Iran may have worked on designing a nuclear warhead, even as world powers and Tehran pursue broader diplomacy to settle a decade-old dispute over its atomic aims.

The silvery-grey soft metal polonium gained notoriety eight years ago in the poisoning of a former Russian spy, Kremlin critic Alexander Litvinenko, in London. The interest of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), a Vienna-based U.N. agency, stems from its potential role in atomic arms.

“The separation of polonium-210, in conjunction with beryllium, can be part of a catalyst for a nuclear chain reaction,” the Arms Control Association, a U.S. research and advocacy group, said on its web site.

It was not immediately clear why Amano would bring up polonium-210 now. The IAEA had said in a report as far back as 2008 it had discussed the substance and Iran had answered its questions about it.

Back then, it cited Iran as saying that some of its scientists had proposed a research project on the production of the material in the 1980s but that the chemist working on it left the country before its completion and it was aborted.

The IAEA said in 2008 it had concluded that the Iranian explanations were consistent with its own findings: “The agency considers this question no longer outstanding at this stage.”

Robert Kelley, a former senior IAEA official, said the matter had been settled at the time and that it was a question of “minor experiments that weren’t part of any organized programme”.

Mark Hibbs of the Carnegie Endowment think-tank said one possibility was that the IAEA had received new intelligence information regarding polonium-210. Hibbs said it had been his understanding that the issue was not seen as urgent and essential by the U.N. agency.

IAEA spokeswoman Gill Tudor said it was not a new issue, but an example of one “that the agency is keeping an eye on and that would benefit from further clarification.” Amano referred to it in response to an audience question, Tudor added.

PARALLEL NEGOTIATIONS

An IAEA investigation into Iran’s behavior is running in parallel with new measures to curb Iran’s nuclear programme under a deal negotiated with world powers in November in return for limited easing of U.S. and European Union sanctions.

The big powers’ interim agreement focused mainly on preventing Tehran obtaining nuclear fissile material to assemble a future bomb, rather than on the question of whether Iran sought atom bomb technology in the past.

The U.N. body has made clear it wants Iran to start addressing long-standing allegations that it may have researched how to make a nuclear bomb, a charge it denies.

Amano’s statement offered a hint that polonium-210 may be among topics it wants to discuss at the February 8 meeting: “Polonium can be used for civil purposes like nuclear batteries, but can also be used for a neutron source for nuclear weapons. We would like to clarify this issue too,” he said.

A U.S. think-tank, the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), said Iran had admitted to producing small amounts of polonium-210 in a Tehran research reactor in the early 1990s.

“Iran claims that the polonium was produced as part of a study of the production of neutron sources for use in radioisotope thermoelectric generators and not for use in a nuclear weapons neutron initiator,” it added on its web site.

Often strained in the past, ties between Iran and the IAEA have improved since last year’s election of a relative moderate, Hassan Rouhani, as new Iranian president on a platform to ease Tehran’s international isolation.

The IAEA’s investigation into what it calls the possible military dimensions to Iran’s nuclear programme is separate from, though still closely linked to, the more wide-ranging negotiations between Tehran and the six major states – the United States, Russia, China, France, Britain and Germany.

Under an agreement signed just weeks before the powers reached their own agreement to cap Iran’s nuclear activity, the U.N. agency has already visited a heavy water production plant and a uranium mine in Iran. However, those first steps do not go to the heart of the IAEA’s investigation.

Western diplomats say the U.N. body’s investigation will be taken into account during talks, due to start on February 18, between Iran and the major powers on a long-term agreement to scale back Iran’s nuclear programme in exchange for a lifting of sanctions.

(Editing by Peter Graff)